Progress report: February 2017

This report was a little late (it is March 4th). This is partially because the end of February snuck up on me – whose idea was a 28 day month, anyway? It is partially because I’ve been busy working on stuff. This report will be much shorter than last months for both reasons. You can read last month’s report here, and next month’s report as it is shaping up here.

I mention a lot of things in here that I could go into much greater detail on. If you are curious about the reasons behind any of this, or want references or resources, let me know in the comments. I don’t have time to go into detail on everything right now, but I certainly have time to go into some of the topics if it would be helpful to anyone.

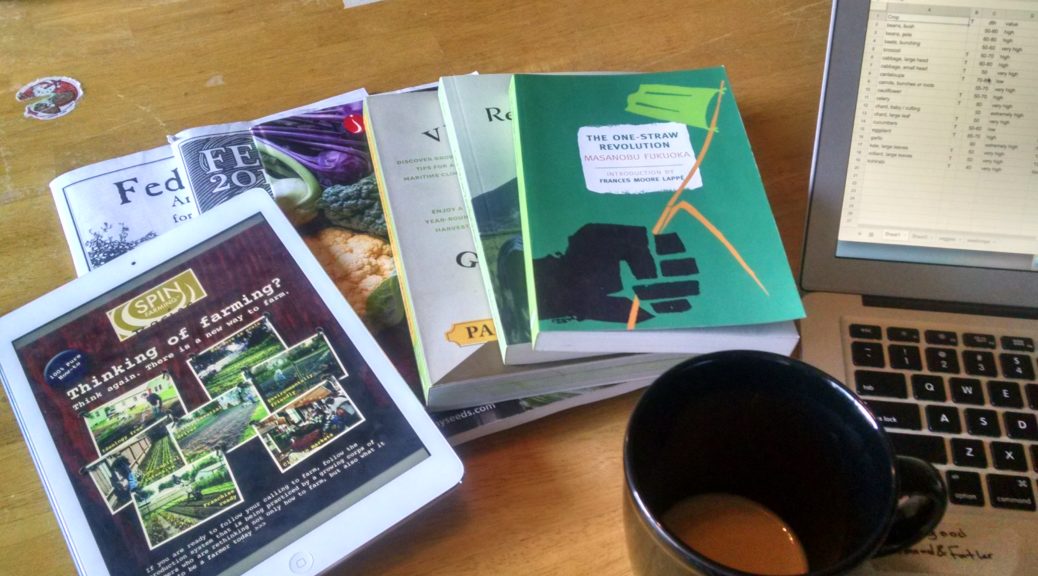

[The picture is some seeds from Baker Creek, and from a local seed swap. This is a small portion of what we are planting this year!]

Summary

Overall, this is incredibly exciting. Spring is coming, and things are very quickly falling into place and becoming real. It is also very intimidating – there are so many unknowns, so many things to learn, and so much work to be done. Sometimes I feel like we are on top of the world, and sometimes I feel like I am in waaaay over my head and that the entire project is going to collapse in complete failure. I’ve done the entrepreneurial roller coaster before, so I’m pretty good at acknowledging the feelings for what they are and keeping my head down and just getting the work done.

But it would be dishonest if I didn’t admit that this is a roller coaster, and that it is hard. I’m looking forward to next year when we will be spending a higher percentage of our time refining things rather than beginning everything from scratch. 🙂

Expenses: $216.18

The only expenses this month were for seeds and other plant material. Overall, the seed budget is significantly higher this year than it will likely be in the future because (1) we are trying a bunch of varieties to see what grows best and sells best here, and (2) in the future we will primarily be growing seeds we saved ourselves, or swapped for. This month brings our total expenses to $579.18.

$32.95 Seeds from Mariseeds bred by Chris Homanics

$51.24 Seeds from Baker Creek Rare Seeds

$55 Seeds from Carol Deppe/Fertile Valley Seeds

$32 Seeds, Sunroots, and cactus pads from Joseph Lofthouse

$18.50 Purple Tree Collard cuttings from happycatseedandc0mpany on ebay

$16.49 Daubenton kale plant from park5500 on ebay

$6.88 Green Giant tree collard cuttings from 888forsale888 on ebay

Work Done

- Stumbled on some interesting ideas that combine community development and marketing: packaging food as meal kits, and organizing supper swaps. I’ll write more on this later, but the basic idea is to get our community eating more food made from scratch by organizing a cooking co-op, and providing food in bulk packages with recipes designed to be convenient as meals for those co-ops. It is more affordable to cook food from scratch, and as farmers if we can sell food in fewer transactions of larger sizes we can provide a better price, and if we make it convenient for people to eat our food then people can spend less money on expensive processed foods, and afford our produce more easily. It all adds up to making the food more affordable and accessible from a number of angles, and is a key part of our strategy to compete with Walmart.

- Planned out permanent cover crops for the vegetable beds.

- Mostly finished choosing varieties and ordering seeds: I poured over catalogs from all the local seed companies I could find, looking for crops that would likely grow well in our cool maritime climate, and that would hopefully sell well. I’ve also gotten some seeds from independent plant breeders that I’ve met online.

- Worked out a ton of details with Mary Anne about the land use and how operations at the farm will go. It is a bit more complicated than just using someone’s yard, because we will be using a pasture at their equestrian facility, and are hoping to have the farm be as open as possible as a demonstration site, and those two factors combined mean that there are a lot of logistical details to make it all safe and smoothly operating. We are just about ready to sign the paperwork and get moving.

- Researched legalities and logistics. We will not need a permit for the farmstand, but it does need to have legally adequate parking and offset from the road. I need to research the laws about signs a bit more to see what exactly we are allowed in terms of roadside signage.

- Made progress planning the installation of infrastructure. We found a source of inexpensive crushed concrete to make the driveway and parking area for the farm stand, and an inexpensive source of compost to jump start the garden beds.

- Made progress planning and researching dry farming and microbe inoculations, which we will be experimenting with heavily as a way to potentially bring areas into garden beds with extremely minimal inputs from outside. Many more details on this later!

- Planted some onion seeds in milk jugs… and decided that we don’t want to plant anything more in milk jugs because it is kind of a bother, and not going to scale anywhere close to what we will need.

- Brought on our first partner – Neil will be helping out on the farm. We’ve known Neil for almost a decade, and he is a very good worker and very smart, so are tickled pink to have him on the team. His primary goal is to learn, and was willing to work for no money, but for us, operating sustainably means that we should pay people who are working on the farm. Also, we don’t want to get nailed by the government for violating labor laws. The sticking point was that we don’t have money coming in yet, and therefore don’t have money to pay him with. After digging into the laws, we found a simple solution to keep everything in line with our values and the laws of the land: add him as a member to the LLC, with a percentage stake based on the estimated percentage of the work he’ll be putting in this year.

- Found some excellent resources for bed planning. Unfortunately haven’t been able to make as much use of them as I wanted to because there are so many unknowns right now. Hopefully we will be able to do more of this next year:http://www.joshvolk.com/Q%26A/spreadsheetsforc.htmlhttp://www.joshvolk.com/Q%26A/fieldmaps.htmlhttps://www.dropbox.com/sh/utl1a5vdfu9uyqn/AsjKSNi7yshttp://www.brookfieldfarm.org/nitty-gritty-crop-planning

Coming up

- Build the basic infrastructure at the farm: clear the access way, put in a driveway, build the farmstand, prepare planting areas.

- Start outreach and marketing to build community around the farm. Put together a Facebook page and website, and start posting content.

- Design the farm branding: logo, brand name, mission statement, business cards, etc

- Make posters and flyers

- Plant early spring greens and herbs, probably with low tunnels for quick and easy season extension.

- Research Good Agricultural Practices and make sure our operations are following them and are safe.